October 30, 2005

Shine on You Crazy Diamond!

In summary, here is how we create your LifeGem diamond...

Step 1. Carbon Capture - After extensive research and development, we have discovered how to extract the carbon from existing cremated remains. This process begins with a portion of remains from any standard cremation.

Step 2. Purification - Once captured, this carbon is heated to extremely high temperatures under special conditions. While removing the existing ash, this process converts your loved one's carbon to graphite with unique characteristics and elements that will create your one-of-a-kind LifeGem diamond like no other in this world.

Step 3. Creation - To create your own, visit Gemological Institute of America (GIA) . The world's finest jewelers use this same certification process.

A diamond that takes millions of years to occur naturally can now be created from the carbon of your loved one in about twenty-four weeks. (Blue LifeGem diamonds may take longer.)October 29, 2005

The Inner Life of Korean Buddhas

Who would have thunk that those wonderfully peaceful statues of Bodhisatvas hide diamonds and pearls, scriptures and hidden relics? Well, the French guy Rudolphe Gombergh (nothing sacré; for those guys) X-rayed some of the statues and discovered plenty of hollow spaces, precious stones etc. As Wired correspondent put it, now we may know why the heck these Buddhas have such a mysterious smile on their faces.

Visit the site devoted to this wonderful exhibition that occured in Paris recently (ok, ok! So skip all the French words and look at the pictures, for crying out loud!), and which should be on its way to San Francisco and NYC.

LCD RIP

The VIDSTONE Serenity

Panel is the first product of its kind. Utilizing unique patent pending technology, the Panel provides families the option of viewing a special, customized multimedia tribute right at their loved one's place of rest. This one of a kind memorial consists of a 7" LCD Panel that may be attached to almost any upright or slanted gravesite monument, including gravestones, mausoleums and columbariums. It features a 5-8 minute photo slideshow detailing the most precious memories of your loved one's life. Visit the company's website

Teenager Shot by Police After iPod Robbery

By MICHELLE O'DONNELL and WILLIAM K. RASHBAUM

Published: October 26, 2005

A Brooklyn teenager matching the description of someone who had just committed an armed robbery was in stable condition last night after being shot twice by two police lieutenants, the police said. The shooting occurred about 7 p.m. on Dean Street near Carlton Avenue, after four men, one of whom brandished what looked like a silver handgun with a black grip, approached a man outside a liquor store at Flatbush and St. Marks Avenues and demanded his iPod, according to a police official, speaking on condition of anonymity because the investigation was in its earliest stages. Nearby on Dean Street at Carlton Avenue, the lieutenants, both plainclothes officers assigned to the 77th Precinct, were on patrol in an unmarked vehicle when they heard the description and realized that it matched that of Mr. Higgins, whom they saw walking on Dean Street, the official said.

The lieutenants chased after him. One ran after Mr. Higgins, who was heading eastbound on Dean Street, while the other drove after him and then pulled the car up onto the curb in front of a building at 618 Dean Street to prevent Mr. Higgins from going inside, the police said. At some point outside the building, Mr. Higgins displayed what looked like a gun, the official said.

The lieutenant running after Mr. Higgins fired 15 shots. It was not clear last night if Mr. Higgins was struck by any of them. The lieutenant in the car then ran after Mr. Higgins, who was backtracking and running west on Dean Street. That officer shot at Mr. Higgins seven times before tackling him at Carlton Avenue and Dean Street, the official said. see the full New York Times article here

Labels: New York Times

Santiago Calatrava

On October 18th, an exceptional exhibition opened at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. A model of HSB Turning Torso as well as its original, the sculpture “Twisting Torso”, will be on display. The production will showcase that many of Santiago Calatrava’s famous and celebrated buildings originated in his independent works of art.Santiago Calatrava is the architect behind HSB Turning Torso. Having worked with a great number of amazing projects, he is one of the most fascinating architects of our time. In addition to his architectual work, Calatrava spends much of his time drawing and conceiving sculptures. The exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art will be the first one of its kind in the United States to feature such a large selection of Calatrava’s independent work and to examine it in conjunction with his architecture.Santiago Calatrava: Sculpture into Architecture is the name of the exhibition that opens at the Metropolitan Museum of Art on October 18, 2005. On view through January 22, 2006, will demonstrate that many of the forms of his celebrated buildings originated in his independent works of art. It includes approximately two dozen sculptures in marble and bronze, many drawings, and 12 architectural models. A model of HSB Turning Torso will be on display as well as its original, the sculpture “Twisting Torso”.HSB Turning Torso began as a sculpture by Santiago Calatrava. Its design was inspired by the human body in a twisting movement. From this original sculpture in white marble, called “Twisting Torso”, HSB Malmö has developed one of Europe’s most exciting residential buildings.- We are very honored to be a part of an exhibition of this kind, says Anja Tragardh, the PR Director of HSB Turning Torso. This shows that we are world-renowned for our project. We are also convinced that the tenants of HSB Turning Torso will be proud that their residence is represented in this category of events, Anja Tragardh concludes.

See also Calatrava's official web site; his unofficial web site; the building's web site You can also read an article about Calatrava in the latest issue of New Yorker.

Humans as Software

Having read the previous post in this blog, I realized that humans themselves can be thought of as software. Every ten years or so we do get a major upgrade, so each decade can be assigned a major version number (as in 1.x, 2.x etc.). The first 10 years or so, the so-called pre-pubescent years reflect our first attempt at everything, so definitely, these are the alpha- and beta-years, or as some programmers mark them version 0.1, 0.5, 0.8, etc.

After puberty hits home, we now acquire so many more and so fundamentally improved features, that one cannot doubt - this is a major new version. We are ready to face the world, to do our little self-promotion, establish a market presence, win over some customers, discover major bugs in our personalities, learn how to apply quick fixes (discovery of alcohol, tobacco and drugs act as service packs).

So by the time we graduate into the real world, with our diplomas safely in our drawers, we can claim to be a version 2.0. Now that's where the fun begins. We now know there are other contenders, there are copycats, there are cheap knock-offs, etc. We consider merging with other software pieces, and always think of looking, just peeking into other people's code.

Few applications survive until the version 12.0 or 13.0. The rarest exceptions would be AutoDesk, SPSS, SAS and probably some other freaks of nature. Most packages shrivel by the time they reach version 5.0.

But then this is nothing but a metaphor gone wrong, isn't it? :)

October 28, 2005

Remote Control For Humans?

We wield remote controls to turn things on and off, make them advance, make them halt. Ground-bound pilots use remotes to fly drone airplanes, soldiers to maneuver battlefield robots. But manipulating humans? Prepare to be remotely controlled. I was. Just imagine being rendered the rough equivalent of a radio-controlled toy car. Nippon Telegraph & Telephone Corp., Japans top telephone company, says it is developing the technology to perhaps make video games more realistic. But more sinister applications also come to mind.I can envision it being added to militaries' arsenals of so-called "non-lethal" weapons. A special headset was placed on my cranium by my hosts during a recent demonstration at an NTT research center. It sent a very low voltage electric current from the back of my ears through my head — either from left to right or right to left, depending on which way the joystick on a remote-control was moved.I found the experience unnerving and exhausting: I sought to step straight ahead but kept careening from side to side. Those alternating currents literally threw me off. The technology is called galvanic vestibular stimulation — essentially, electricity messes with the delicate nerves inside the ear that help maintain balance.I felt a mysterious, irresistible urge to start walking to the right whenever the researcher turned the switch to the right. I was convinced — mistakenly — that this was the only way to maintain my balance. The phenomenon is painless but dramatic. Your feet start to move before you know it. I could even remote-control myself by taking the switch into my own hands.There's no proven-beyond-a-doubt explanation yet as to why people start veering when electricity hits their ear. But NTT researchers say they were able to make a person walk along a route in the shape of a giant pretzel using this technique. It's a mesmerizing sensation similar to being drunk or melting into sleep under the influence of anesthesia. But it's more definitive, as though an invisible hand were reaching inside your brain.NTT says the feature may be used in video games and amusement park rides, although there are no plans so far for a commercial product. Some people really enjoy the experience, researchers said while acknowledging that others feel uncomfortable. I watched a simple racing-car game demonstration on a large screen while wearing a device programmed to synchronize the curves with galvanic vestibular stimulation. It accentuated the swaying as an imaginary racing car zipped through a virtual course, making me wobbly.Another program had the electric current timed to music. My head was pulsating against my will, getting jerked around on my neck. I became so dizzy I could barely stand. I had to turn it off. NTT researchers suggested this may be a reflection of my lack of musical abilities. People in tune with freely expressing themselves love the sensation, they said."We call this a virtual dance experience although some people have mentioned it's more like a virtual drug experience," said Taro Maeda, senior research scientist at NTT. "I'm really hopeful Apple Computer will be interested in this technology to offer it in their iPod."Research on using electricity to affect human balance has been going on around the world for some time. James Collins, professor of biomedical engineering at Boston University, has studied using the technology to prevent the elderly from falling and to help people with an impaired sense of balance. But he also believes the effect is suited for games and other entertainment. "I suspect they'll probably get a kick out of the illusions that can be created to give them a more total immersion experience as part of virtual reality," Collins said.The very low level of electricity required for the effect is unlikely to cause any health damage, Collins said. Still, NTT required me to sign a consent form, saying I was trying the device at my own risk.And risk definitely comes to mind when playing around with this technology. Timothy Hullar, assistant professor at the Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, Mo., believes finding the right way to deliver an electromagnetic field to the ear at a distance could turn the technology into a weapon for situations where "killing isn't the best solution.""This would be the most logical situation for a nonlethal weapon that presumably would make your opponent dizzy," he said via e-mail. "If you find just the right frequency, energy, duration of application, you would hope to find something that doesn't permanently injure someone but would allow you to make someone temporarily off-balance."Indeed, a small defense contractor in Texas, Invocon Inc., is exploring whether precisely tuned electromagnetic pulses could be safely fired into people's ears to temporarily subdue them. NTT has friendlier uses in mind. If the sensation of movement can be captured for playback, then people can better understand what a ballet dancer or an Olympian gymnast is doing, and that could come handy in teaching such skills. And it may also help people dodge oncoming cars or direct a rescue worker in a dark tunnel, NTT researchers say. They maintain that the point is not to control people against their will.If you're determined to fight the suggestive orders from the electric currents by clinging to a fence or just lying on your back, you simply won't move. But from my experience, if the currents persist, you'd probably be persuaded to follow their orders. And I didn't like that sensation. At all.

We wield remote controls to turn things on and off, make them advance, make them halt. Ground-bound pilots use remotes to fly drone airplanes, soldiers to maneuver battlefield robots. But manipulating humans? Prepare to be remotely controlled. I was. Just imagine being rendered the rough equivalent of a radio-controlled toy car. Nippon Telegraph & Telephone Corp., Japans top telephone company, says it is developing the technology to perhaps make video games more realistic. But more sinister applications also come to mind.I can envision it being added to militaries' arsenals of so-called "non-lethal" weapons. A special headset was placed on my cranium by my hosts during a recent demonstration at an NTT research center. It sent a very low voltage electric current from the back of my ears through my head — either from left to right or right to left, depending on which way the joystick on a remote-control was moved.I found the experience unnerving and exhausting: I sought to step straight ahead but kept careening from side to side. Those alternating currents literally threw me off. The technology is called galvanic vestibular stimulation — essentially, electricity messes with the delicate nerves inside the ear that help maintain balance.I felt a mysterious, irresistible urge to start walking to the right whenever the researcher turned the switch to the right. I was convinced — mistakenly — that this was the only way to maintain my balance. The phenomenon is painless but dramatic. Your feet start to move before you know it. I could even remote-control myself by taking the switch into my own hands.There's no proven-beyond-a-doubt explanation yet as to why people start veering when electricity hits their ear. But NTT researchers say they were able to make a person walk along a route in the shape of a giant pretzel using this technique. It's a mesmerizing sensation similar to being drunk or melting into sleep under the influence of anesthesia. But it's more definitive, as though an invisible hand were reaching inside your brain.NTT says the feature may be used in video games and amusement park rides, although there are no plans so far for a commercial product. Some people really enjoy the experience, researchers said while acknowledging that others feel uncomfortable. I watched a simple racing-car game demonstration on a large screen while wearing a device programmed to synchronize the curves with galvanic vestibular stimulation. It accentuated the swaying as an imaginary racing car zipped through a virtual course, making me wobbly.Another program had the electric current timed to music. My head was pulsating against my will, getting jerked around on my neck. I became so dizzy I could barely stand. I had to turn it off. NTT researchers suggested this may be a reflection of my lack of musical abilities. People in tune with freely expressing themselves love the sensation, they said."We call this a virtual dance experience although some people have mentioned it's more like a virtual drug experience," said Taro Maeda, senior research scientist at NTT. "I'm really hopeful Apple Computer will be interested in this technology to offer it in their iPod."Research on using electricity to affect human balance has been going on around the world for some time. James Collins, professor of biomedical engineering at Boston University, has studied using the technology to prevent the elderly from falling and to help people with an impaired sense of balance. But he also believes the effect is suited for games and other entertainment. "I suspect they'll probably get a kick out of the illusions that can be created to give them a more total immersion experience as part of virtual reality," Collins said.The very low level of electricity required for the effect is unlikely to cause any health damage, Collins said. Still, NTT required me to sign a consent form, saying I was trying the device at my own risk.And risk definitely comes to mind when playing around with this technology. Timothy Hullar, assistant professor at the Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, Mo., believes finding the right way to deliver an electromagnetic field to the ear at a distance could turn the technology into a weapon for situations where "killing isn't the best solution.""This would be the most logical situation for a nonlethal weapon that presumably would make your opponent dizzy," he said via e-mail. "If you find just the right frequency, energy, duration of application, you would hope to find something that doesn't permanently injure someone but would allow you to make someone temporarily off-balance."Indeed, a small defense contractor in Texas, Invocon Inc., is exploring whether precisely tuned electromagnetic pulses could be safely fired into people's ears to temporarily subdue them. NTT has friendlier uses in mind. If the sensation of movement can be captured for playback, then people can better understand what a ballet dancer or an Olympian gymnast is doing, and that could come handy in teaching such skills. And it may also help people dodge oncoming cars or direct a rescue worker in a dark tunnel, NTT researchers say. They maintain that the point is not to control people against their will.If you're determined to fight the suggestive orders from the electric currents by clinging to a fence or just lying on your back, you simply won't move. But from my experience, if the currents persist, you'd probably be persuaded to follow their orders. And I didn't like that sensation. At all.

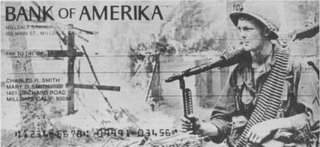

LRB: We do not deserve these people

By Anatol Lieven

The New American Militarism:

How Americans Are Seduced by War by Andrew Bacevich

[ Buy from the London Review Bookshop ] · Oxford, 270 pp, £16.99

A key justification of the Bush administration’s purported strategy of ‘democratising’ the Middle East is the argument that democracies are pacific, and that Muslim democracies will therefore eventually settle down peacefully under the benign hegemony of the US. Yet, as Andrew Bacevich points out in one of the most acute analyses of America to have appeared in recent years, the United States itself is in many ways a militaristic country, and becoming more so:at the end of the Cold War, Americans said yes to military power. The scepticism about arms and armies that informed the original Wilsonian vision, indeed, that pervaded the American experiment from its founding, vanished. Political leaders, liberals and conservatives alike, became enamoured with military might.

The ensuing affair had, and continues to have, a heedless, Gatsby-like aspect, a passion pursued in utter disregard of any consequences that might ensue.The president’s title of ‘commander-in-chief’ is used by administration propagandists to suggest, in a way reminiscent of German militarists before 1914 attempting to defend their half-witted kaiser, that any criticism of his record in external affairs comes close to a betrayal of the military and the country. Compared to German and other past militarisms, however, the contemporary American variant is extremely complex, and the forces that have generated it have very diverse origins and widely differing motives: The new American militarism is the handiwork of several disparate groups that shared little in common apart from being intent on undoing the purportedly nefarious effects of the 1960s. Military officers intent on rehabilitating their profession; intellectuals fearing that the loss of confidence at home was paving the way for the triumph of totalitarianism abroad; religious leaders dismayed by the collapse of traditional moral standards; strategists wrestling with the implications of a humiliating defeat that had undermined their credibility; politicians on the make; purveyors of pop culture looking to make a buck: as early as 1980, each saw military power as the apparent answer to any number of problems.

<read more

Two other factors have also been critical: the dependence on imported oil is seen as requiring American hegemony over the Middle East; and the Israel lobby has worked assiduously and with extraordinary success to make sure that Israel’s enemies are seen by Americans as also being those of the US. And let’s not forget the role played by the entrenched interests of the military itself and what Dwight Eisenhower once denounced as the ‘military-industrial-academic complex’.The security elites are obviously interested in the maintenance and expansion of US global military power, if only because their own jobs and profits depend on it. Jobs and patronage also ensure the support of much of the Congress, which often authorises defence spending on weapons systems the Pentagon doesn’t want and hasn’t asked for, in order to help some group of senators and congressmen in whose home states these systems are manufactured. To achieve wider support in the media and among the public, it is also necessary to keep up the illusion that certain foreign nations constitute a threat to the US, and to maintain a permanent level of international tension.

That’s not the same, however, as having an actual desire for war, least of all for a major conflict which might ruin the international economy. US ground forces have bitter memories of Vietnam, and no wish to wage an aggressive war: Rumsfeld and his political appointees had to override the objections of the senior generals, in particular those of the army chief of staff, General Eric Shinseki, before the attack on Iraq. The navy and air force do not have to fight insurgents in hell-holes like Fallujah, and so naturally have a more relaxed attitude.To understand how the Bush administration was able to manipulate the public into supporting the Iraq war one has to look for deeper explanations. They would include the element of messianism embodied in American civic nationalism, with its quasi-religious belief in the universal and timeless validity of its own democratic system, and in its right and duty to spread that system to the rest of the world. This leads to a genuine belief that American soldiers can do no real wrong because they are spreading ‘freedom’.

Also of great importance – at least until the Iraqi insurgency rubbed American noses in the horrors of war – has been the development of an aesthetic that sees war as waged by the US as technological, clean and antiseptic; and thanks to its supremacy in weaponry, painlessly victorious. Victory over the Iraqi army in 2003 led to a new flowering of megalomania in militarist quarters. The amazing Max Boot of the Wall Street Journal – an armchair commentator, not a frontline journalist – declared that the US victory had made ‘fabled generals such as Erwin Rommel and Heinz Guderian seem positively incompetent by comparison’. Nor was this kind of talk restricted to Republicans. More than two years into the Iraq quagmire, strategic thinkers from the Democratic establishment were still declaring that ‘American military power in today’s world is practically unlimited.’Important sections of contemporary US popular culture are suffused with the language of militarism. Take Bacevich on the popular novelist Tom Clancy:In any Clancy novel, the international order is a dangerous and threatening place, awash with heavily armed and implacably determined enemies who threaten the United States.

That Americans have managed to avoid Armageddon is attributable to a single fact: the men and women of America’s uniformed military and its intelligence services have thus far managed to avert those threats. The typical Clancy novel is an unabashed tribute to the skill, honour, extraordinary technological aptitude and sheer decency of the nation’s defenders. To read Red Storm Rising is to enter a world of ‘virtuous men and perfect weapons’, as one reviewer noted. ‘All the Americans are paragons of courage, endurance and devotion to service and country. Their officers are uniformly competent and occasionally inspired. Men of all ranks are faithful husbands and devoted fathers.’ Indeed, in the contract that he signed for the filming of Red October, Clancy stipulated that nothing in the film show the navy in a bad light.Such attitudes go beyond simply glorying in violence, military might and technological prowess. They reflect a belief – genuine or assumed – in what the Germans used to call Soldatentum: the pre-eminent value of the military virtues of courage, discipline and sacrifice, and explicitly or implicitly the superiority of these virtues to those of a hedonistic, contemptible and untrustworthy civilian society and political class.

In the words of Thomas Friedman, the ostensibly liberal foreign affairs commentator of the ostensibly liberal New York Times, ‘we do not deserve these people. They are so much better than the country . . . they are fighting for.’ Such sentiments have a sinister pedigree in modern history.In the run-up to the last election, even a general as undistinguished as Wesley Clark could see his past generalship alone as qualifying him for the presidency – and gain the support of leading liberal intellectuals. Not that this was new: the first president was a general and throughout the 19th and 20th centuries both generals and more junior officers ran for the presidency on the strength of their military records. And yet, as Bacevich points out, this does not mean that the uniformed military have real power over policy-making, even in matters of war. General Tommy Franks may have regarded Douglas Feith, the undersecretary of defense, as ‘the stupidest fucking guy on the planet’, but he took Feith’s orders, and those of the civilians standing behind him: Wolfowitz, Cheney, Rumsfeld and the president himself. Their combination of militarism and contempt for military advice recalls Clemenceau and Churchill – or Hitler and Stalin.

Indeed, a portrait of US militarism today could be built around a set of such apparently glaring contradictions: the contradiction, for example, between the military coercion of other nations and the belief in the spreading of ‘freedom’ and ‘democracy’. Among most non-Americans, and among many American realists and progressives, the collocation seems inherently ludicrous. But, as Bacevich brings out, it has deep roots in American history. Indeed, the combination is historically coterminous with Western imperialism. Historians of the future will perhaps see preaching ‘freedom’ at the point of an American rifle as no less morally and intellectually absurd than ‘voluntary’ conversion to Christianity at the point of a Spanish arquebus.Its symbols may be often childish and its methods brutish, but American belief in ‘freedom’ is a real and living force. This cuts two ways. On the one hand, the adherence of many leading intellectuals in the Democratic Party to a belief in muscular democratisation has had a disastrous effect on the party’s ability to put up a strong resistance to the policies of the administration.

Bush’s messianic language of ‘freedom’ – supported by the specifically Israeli agenda of Natan Sharansky and his allies in the US – has been all too successful in winning over much of the opposition. On the other hand, the fact that a belief in freedom and democracy lies at the heart of civic nationalism places certain limits on American imperialism – weak no doubt, but nonetheless real. It is not possible for the US, unlike previous empires, to pursue a strategy of absolutely unconstrained Machtpolitik. This has been demonstrated recently in the breach between the Bush administration and the Karimov tyranny in Uzbekistan.

The most important contradiction, however, is between the near worship of the military in much of American culture and the equally widespread unwillingness of most Americans – elites and masses alike – to serve in the armed forces. If people like Friedman accompanied their stated admiration for the military with a real desire to abandon their contemptible civilian lives and join the armed services, then American power in the world really might be practically unlimited. But as Bacevich notes,having thus made plain his personal disdain for crass vulgarity and support for moral rectitude, Friedman in the course of a single paragraph drops the military and moves on to other pursuits. His many readers, meanwhile, having availed themselves of the opportunity to indulge, ever so briefly, in self-loathing, put down their newspapers and themselves move on to other things. Nothing has changed, but columnist and readers alike feel better for the cathartic effect of this oblique, reassuring encounter with an alien world.

Today, having dissolved any connection between claims to citizenship and obligation to serve, Americans entrust their security to a class of military professionals who see themselves in many respects as culturally and politically set apart from the rest of society. This combination of a theoretical adulation with a profound desire not to serve is not of course new. It characterised most of British society in the 19th century, when, just as with the US today, the overwhelming rejection of conscription – until 1916 – meant that, appearances to the contrary, British power was far from unlimited. The British Empire could use its technological superiority, small numbers of professional troops and local auxiliaries to conquer backward and impoverished countries in Asia and Africa, but it would not have dreamed of intervening unilaterally in Europe or North America.Despite spending more on the military than the rest of the world combined, and despite enjoying overwhelming technological superiority, American military power is actually quite limited. As Iraq – and to a lesser extent Afghanistan – has demonstrated, the US can knock over states, but it cannot suppress the resulting insurgencies, even one based in such a comparatively small population as the Sunni Arabs of Iraq.

As for invading and occupying a country the size of Iran, this is coming to seem as unlikely as an invasion of mainland China.In other words, when it comes to actually applying military power the US is pretty much where it has been for several decades. Another war of occupation like Iraq would necessitate the restoration of conscription: an idea which, with Vietnam in mind, the military detests, and which politicians are well aware would probably make them unelectable. It is just possible that another terrorist attack on the scale of 9/11 might lead to a new draft, but that would bring the end of the US military empire several steps closer. Recognising this, the army is beginning to imitate ancient Rome in offering citizenship to foreign mercenaries in return for military service – something that the amazing Boot approves, on the grounds that while it helped destroy the Roman Empire, it took four hundred years to do so.Facing these dangers squarely, Bacevich proposes refocusing American strategy away from empire and towards genuine national security. It is a measure of the degree to which imperial thinking now dominates US politics that these moderate and commonsensical proposals would seem nothing short of revolutionary to the average member of the Washington establishment.

They include a renunciation of messianic dreams of improving the world through military force, except where a solid international consensus exists in support of US action; a recovery by Congress of its power over peace and war, as laid down in the constitution but shamefully surrendered in recent years; the adoption of a strategic doctrine explicitly making war a matter of last resort; and a decision that the military should focus on the defence of the nation, not the projection of US power. As a means of keeping military expenditure in some relationship to actual needs, Bacevich suggests pegging it to the combined annual expenditure of the next ten countries, just as in the 19th century the size of the British navy was pegged to that of the next two largest fleets – it is an index of the budgetary elephantiasis of recent years that this would lead to very considerable spending reductions.

This book is important not only for the acuteness of its perceptions, but also for the identity of its author. Colonel Bacevich’s views on the military, on US strategy and on world affairs were profoundly shaped by his service in Vietnam. His year there ‘fell in the conflict’s bleak latter stages . . . long after an odour of failure had begun to envelop the entire enterprise’. The book is dedicated to his brother-in-law, ‘a casualty of a misbegotten war’.Just as Vietnam shaped his view of how the US and the US military should not intervene in the outside world, so the Cold War in Europe helped define his beliefs about the proper role of the military. For Bacevich and his fellow officers in Europe in the 1970s and 1980s, defending the West from possible Soviet aggression, ‘not conquest, regime change, preventive war or imperial policing’, was ‘the American soldier’s true and honourable calling’.In terms of cultural and political background, this former soldier remains a self-described Catholic conservative, and intensely patriotic. During the 1990s Bacevich wrote for right-wing journals, and still situates himself culturally on the right:As long as we shared in the common cause of denouncing the foolishness and hypocrisies of the Clinton years, my relationship with modern American conservatism remained a mutually agreeable one . . . But my disenchantment with what passes for mainstream conservatism, embodied in the Bush administration and its groupies, is just about absolute. Fiscal irresponsibility, a buccaneering foreign policy, a disregard for the constitution, the barest lip service as a response to profound moral controversies: these do not qualify as authentically conservative values.

On this score my views have come to coincide with the critique long offered by the radical left: it is the mainstream itself, the professional liberals as well as the professional conservatives, who define the problem . . . The Republican and Democratic Parties may not be identical, but they produce nearly identical results.Bacevich, in other words, is sceptical of the naive belief that replacing the present administration with a Democrat one would lead to serious changes in the US approach to the world. Formal party allegiances are becoming increasingly irrelevant as far as thinking about foreign and security policy is concerned.Bacevich also makes plain the private anger of much of the US uniformed military at the way in which it has been sacrificed, and its institutions damaged, by chickenhawk civilian chauvinists who have taken good care never to see action themselves; and the deep private concern of senior officers that they might be ordered into further wars that would wreck the army altogether. Now, as never before, American progressives have the chance to overcome the knee-jerk hostility to the uniformed military that has characterised the left since Vietnam, and to reach out not only to the soldiers in uniform but also to the social, cultural and regional worlds from which they are drawn. For if the American left is once again to become an effective political force, it must return to some of its own military traditions, founded on the distinguished service of men like George McGovern, on the old idea of the citizen soldier, and on a real identification with that soldier’s interests and values. With this in mind, Bacevich calls for moves to bind the military more closely into American society, including compulsory education for all officers at a civilian university, not only at the start of their careers but at intervals throughout them.

Or to put it another way, the left must fight imperialism in the name of patriotism. Barring a revolutionary and highly unlikely transformation of American mass culture, any political party that wishes to win majority support will have to demonstrate its commitment to the defence of the country. The Bush administration has used the accusation of weakness in security policy to undermine its opponents, and then used this advantage to pursue reckless strategies that have themselves drastically weakened the US. The left needs to heed Bacevich and draw up a tough, realistic and convincing alternative. It will also have to demonstrate its identification with the respectable aspects of military culture. The Bush administration and the US establishment in general may have grossly mismanaged the threats facing us, but the threats are real, and some at least may well need at some stage to be addressed by military force. And any effective military force also requires the backing of a distinctive military ethic embracing loyalty, discipline and a capacity for both sacrifice and ruthlessness.

In the terrible story of the Bush administration and the Iraq war, one of the most morally disgusting moments took place at a Senate Committee hearing on 29 April 2004, when Paul Wolfowitz – another warmonger who has never served himself – mistook, by a margin of hundreds, how many US soldiers had died in a war for which he was largely responsible. If an official in a Democratic administration had made a public mistake like that, the Republican opposition would have exploited it ruthlessly, unceasingly, to win the next election. The fact that the Democrats completely failed to do this says a great deal about their lack of political will, leadership and capacity to employ a focused strategy.Because they are the ones who pay the price for reckless warmongering and geopolitical megalomania, soldiers and veterans of the army and marine corps could become valuable allies in the struggle to curb American imperialism, and return America’s relationship with its military to the old limited, rational form. For this to happen, however, the soldiers have to believe that campaigns against the Iraq war, and against current US strategy, are anti-militarist, but not anti-military. We have needed the military desperately on occasions in the past; we will definitely need them again.You can find this article on the London Review of Books!Anatol Lieven is a senior research fellow at the New America Foundation in Washington DC and the author of America Right or Wrong: An Anatomy of American Nationalism.

Labels: London Review of Books, LRB

October 27, 2005

Plasma? LCD? Nah - SED!!!

ITworld.com - Canon, Toshiba to start SED production this week

A joint venture established by Canon Inc. and Toshiba Corp. to develop and commercialize a new flat-panel display technology called SED (surface-conduction electron-emitter display) will begin trial production of displays this week. It offers contrast up to 100 000:1 and almost instant refresh!SED technology has been under development for more than 20 years and is being positioned by Canon and Toshiba as a better option for large-screen TVs than PDP (plasma display panel) technology. SED panels can produce pictures that are as bright as CRTs (cathode ray tubes), use up to one-third less power than equivalent size PDPs and don't have the slight time delay sometimes seen with some other flat-panel displays, according to the companies.Canon and Toshiba are hoping to see the first SED televisions available in Japan sometime in the first half of next year.But before those TVs can come to market the companies must be able to mass produce the SED panels. As part of their work towards this goal they established SED Inc. in October last year and committed ¿200 billion (US$1.8 billion) towards SED research, development, production and marketing.Later this week the venture will begin test production of panels at a factory in Hiratsuka City in Kanagawa prefecture, west of Tokyo, said Richard Berger, a spokesman for Canon, on Tuesday. Hiratsuka is where Canon began its development work on SED technology more than 20 years ago and is now home to the joint venture.On Monday Canon announced it will invest ¿20.8 billion to build a new research and development center near the current Hiratsuka plant. The center will be owned by Canon but lent to the SED joint venture, said Berger.Initial plans call for production of around 3,000 SED panels per month. Those panels will be 50-inch class panels, which means they'll be somewhere between 50 inches and 59 inches across the diagonal. Although initially intended only to prove the mass production technology, panels that pass quality tests will likely find their way into the first consumer SED televisions.The test production is expected to continue through 2006 with mass production starting in 2007, according to current plans. That will begin at 15,000 panels per month and increase to 75,000 panels per month by the end of 2007 as Canon and Toshiba aim to grab a 30 percent share of the market for TVs of 50 inches and above.Several display technologies are being promoted by different companies, and which one is most suitable for which type of television depends on who you ask.Most familiar to TV shoppers are LCD (liquid crystal display) and PDP televisions. At present LCD TVs are available up to around 40 inches across the diagonal, and PDPs begin from around 36 inches, but the division is shifting. That's because companies with strengths in the respective technologies are trying to get a greater market share.For example, Samsung Electronics Co. Ltd., which is a leading maker of LCD panels, has already shown an 80-inch LCD panel, although it's not a commercial product.There's also OLED (organic light emitting diode) technology. It's being developed by companies like Seiko Epson Corp. and Samsung Electronics and is also being pushed as a TV display technology, although it has yet to reach commercialization.There are also several projection display technologies, including Texas Instruments Inc.'s DLP (Digital Light Processing), Sony Corp.'s SXRD (Silicon Crystal Reflective Display) and Seiko Epson's 3LCD.

TLS Andrew Parker: Seven Deadly Colours

Darwin's blind spot

by John Tyler Bonner 12 October 2005

review of SEVEN DEADLY COLOURS

The genius of nature's palette and how it eluded Darwin Andrew Parker 336pp.

Free Press. £16.99. | 0 7432 5939 4

The book is organized around specific colours and the different ways in which they are produced. Here, one immediately thinks of pigments, as in a painting, and indeed many animal colours are produced by pigments, but there are other kinds as well, such as the iridescent physical colours that can be seen on the surfaces on some minerals and bird feathers. In the chapter on the colour ultraviolet, Parker asks why kestrels hover over motorway verges, where the prey is well camouflaged. The answer is totally unexpected and very interesting. It revolves around the fact that animals differ in what colours they can see. Some are quite colour-blind and see things only in black and white, such as dolphins and seals, while others, such as birds and insects, can manage better than us. They not only see the range of colours we see, but also into the ultraviolet to which we are blind. The world before them looks quite different from ours, something we can only get an inkling of by special photography that records in ultraviolet. Kestrels have this gift. They prey on voles that are themselves well camouflaged, but voles establish trails and secrete various marking chemicals (mainly in their urine) along their runways, and one of these substances absorbs ultraviolet light. So the kestrel can follow the network of trails, which are abundant along roadways, and pounce on the moving furry balls on the track that they – but not we – can see. The chapter on the colour blue is especially interesting because it involves bioluminescence. Some organisms possess a way of chemically manufacturing light in the dark: the light of fireflies and of many denizens of the oceans: fishes, various invertebrates and unicellular organisms that can be seen in the wake of a boat or the dip of an oar in warm seas. Even some fungi send off a magical glow at night, as do glow worms (insect larvae) of various sorts. This nocturnal activity serves many functions, from attracting mates, or prey, to actually seeing in the dark, a skill acquired by some of those strange abyssal fishes. They carry their headlights below their eyes, but the luminescence comes from symbiotic bacteria that glow in a special chamber that holds them. The bacterial light is on permanently, yet they flash their headlights; they do so by having a membranous shutter over the luminous pocket that the fish can open and close. There has been some very interesting recent work on these luminescent bacteria that has a direct relevance to human pathology. It has been shown that the bacteria can glow only if they are in a group of sufficient numbers, something that is automatically sensed by them. It turns out that this is true for bacterial pathogens as well: they can have their damaging toxic effect only if they are sufficiently numerous to form a quorum. The section on the colour orange includes the particularly interesting example of milk snakes. There are some species found all the way from North to South America that are beautifully banded, with broad bands of white, black and orange. They are extremely conspicuous, which at first seems surprising since they are harmless and have numerous predators. It is assumed that they are to some degree protected because their colouration closely resembles that of coral snakes that are highly venomous. Parker himself has done some ingenious experiments to show that the milk snake has an additional way of eluding predators: it can move very rapidly and reach a speed where the colours become fused into a uniform colour such as green or pink. This happens because the eyes of their predators – birds and mammals – can capture in their eyes and brain only a finite number of images per second, and beyond that the striking bands turn into a blur. Parker elaborates on this in an excellent discussion of mimicry, where an edible species will acquire the marking of a distasteful or dangerous one, as in the case of milk and coral snakes. This was first discovered in butterflies by Henry Bates in the middle of the nineteenth century, deep in the Amazon jungle. A few years later, Fritz Müller found that in some cases the similarly coloured species were all noxious; by flying under the same banner and widely advertising it, they spread the word: “Don’t even think of eating any of us”. In other words, there are two kinds of mimicry: in one, distasteful or poisonous species are imitated by edible and harmless ones to avoid being eaten (Batsesian mimicry); in the other all the forms are unpalatable, and to make this known they all have the same flashy warning colouration (Müllerian mimicry). Animal colour also plays an important role in the selection of mates; the so-called sexual selection was another of Darwin’s major insights. Usually males are the painted ones, often going to extremes, such as the birds of paradise and many others. Sexual selection may be a system to find the most desirable mate, but it has the severe disadvantage of showing the predator where to attack. I am particularly fond of a case (not discussed in the book) where male guppies living in streams where there are no predators will have large and showy spots, while those in predator-infested streams have greatly subdued markings. Many of the colour patterns, as Parker shows, serve as camouflage, making the animal blend in with its natural surroundings. I particularly like the marine forms that become transparent – see-through fishes and shrimp. How can the normal pigments of an animal’s body transform so that they no longer absorb light? It seems to me that it should be a problem of interest to biochemists, but I have been unable to persuade anyone to look into it. Seven Deadly Colours is a book that has a great deal to offer, not only to the interested reader but to the biologist as well. The author makes a valiant attempt to make the physics that surrounds all colour easy and accessible, and when he only partially succeeds, this is no fault of his own. The subject is simply not easy, and he provides enough of it to give a sense of what is relevant. At the end of Seven Deadly Colours: The genius of nature’s palette and how it eluded Darwin, Andrew Parker returns to the idea that complex eyes arose rather suddenly as part of the Cambrian explosion. It is true that in those famous deposits one finds the first fossil eyes, and that they do indeed seem remarkably elaborate. I am more persuaded, in keeping with the recent genetic findings as well as our knowledge of primitive invertebrate eyes, that the process was gradual long before the Cambrian explosion. I have a special attraction to lower beasts and there is a unicellular marine organism (a dinoflagellate) that not only has a light sensitive eyespot (equivalent to our retina with a light absorbing pigment that guides the motile cell towards light) but also a lens capable of focusing the light and producing an image. It is certainly hard to imagine why this elaborate structure arose, and what it does for the animal in its environment, especially as there is nothing equivalent to a brain to process what it sees. It is indeed very puzzling, but then from my own research on social amoebae, I know that we often underestimate the cleverness of simple and primitive organisms.

Labels: TLS

October 26, 2005

French Artist Arman died Oct 22 in New York

Born as Armand Fernandez in 1928 at Nice, the son of an antique dealer. His first lessons in painting were given him by his father. He took his Baccalauréat in philosophy and mathematics in 1946 and began to study painting at the École Nationale d'Art Décoratif, Nice. In 1947 he met Yves Klein and Claude Pascal in Paris and accompanied them on a hitch-hiking tour of Europe. Completing his studies in Nice in 1949, he enrolled as a student at the École du Louvre, where he concentrated on the study of archaeology and oriental art. His pictures at this time were influenced by Surrealism. In 1951 he became a teacher at the Bushido Kai Judo School. He completed his military service as a medical orderly in the Indo-Chinese War. He did abstract paintings in 1953. He took part in actions with Yves Klein, with whom he had been discussing subjects such as Zen Buddhism and astrology since 1947. He married Eliane Radigue. He was impressed by a Kurt Schwitters exhibition in Paris in 1954 which inspired him to begin his work with stamp imprints, the Cachets.

He earned his living during this period through occasional jobs, selling furniture and harpoon fishing. He had his first one-man exhibitions in London and Paris in 1956. In 1957 he travelled in Persia, Turkey and Afghanistan. In 1958 he dropped the "d" in his name, inspired by a printer's error. He started his monotypes using objects, his Allures. In 1959 he did his first Accumulations and Poubelles. The Accumulations were assemblages of everyday objects and similar consumer articles displayed in boxes. The Poubelles were similar, but used collections of rubbish.

In 1960 he became a founding member of the Nouveaux Réalistes. Through this group he made contact with members of the Zero group. He showed in New York and Milan in 1961 and made his sliced and smashed objects (Couples, Colères). In 1962 he showed in various European cities and also in Los Angeles, where he was assisted by Edward Kienholz. He started his so-called Combustions, or burned objects, in 1963. He also took up part-time residence in New York. In 1964 he had his first museum retrospectives at the Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, and at the Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam. Polyester now became his most important material. In 1965 and 1966 he was given large retrospective exhibitions in Krefeld, Lausanne, Paris, Venice and Brussels. In 1967 he initiated a collaboration between art and industry with the company Renault and represented France at "Expo '67", Montreal. He showed at the Venice Biennale and at documenta "4" in Kassel in 1968, and was given a teaching post at the University of California, Los Angeles. In 1970 he began his Accumulations in concrete and exhibited at the World's Fair in Osaka. In 1971 he began a series with organic garbage embedded in plastic. In 1972 he gained American citizenship in addition to his French nationality. In 1974 he toured with a retrospective through five North American cities, and returned to Paris. Since 1975 he has lived in New York - where he has a studio - and in Paris. Died October 22, 2005 in New York.

Visit also Arman Studio

Prokudin-Gorksiy: Photographer to the Tsar

The photographs of Sergei Mikhailovich Prokudin-Gorskii (1863-1944) offer a vivid portrait of a lost world--the Russian Empire on the eve of World War I and the coming revolution. His subjects ranged from the medieval churches and monasteries of old Russia, to the railroads and factories of an emerging industrial power, to the daily life and work of Russia's diverse population.

In the early 1900s Prokudin-Gorskii formulated an ambitious plan for a photographic survey of the Russian Empire that won the support of Tsar Nicholas II. Between 1909-1912, and again in 1915, he completed surveys of eleven regions, traveling in a specially equipped railroad car provided by the Ministry of Transportation.

Prokudin-Gorskii left Russia in 1918, going first to Norway and England before settling in France. By then, the tsar and his family had been murdered and the empire that Prokudin-Gorskii so carefully documented had been destroyed. His unique images of Russia on the eve of revolution--recorded on glass plates--were purchased by the Library of Congress in 1948 from his heirs. For this exhibition, the glass plates have been scanned and, through an innovative process known as digichromatography, brilliant color images have been produced. This exhibition features a sampling of Prokudin-Gorskii's historic images produced through the new process; the digital technology that makes these superior color prints possible; and celebrates the fact that for the first time many of these wonderful images are available to the public.

Born in St. Petersburg in 1863 and educated as a chemist, Prokudin-Gorskii devoted his career to the advancement of photography. He studied with renowned scientists in St. Petersburg, Berlin, and Paris. His own original research yielded patents for producing color film slides and for projecting color motion pictures. Around 1907 Prokudin-Gorskii envisioned and formulated a plan to use the emerging technological advancements that had been made in color photography to systematically document the Russian Empire. Through such an ambitious project, his ultimate goal was to educate the schoolchildren of Russia with his "optical color projections" of the vast and diverse history, culture, and modernization of the empire. Outfitted with a specially equipped railroad car darkroom provided by Tsar Nicholas II, and in possession of two permits that granted him access to restricted areas and cooperation from the empire's bureaucracy, Prokudin-Gorskii documented the Russian Empire around 1907 through 1915. He conducted many illustrated lectures of his work. Prokudin-Gorskii left Russia in 1918, after the Russian Revolution, and eventually settled in Paris, where he died in 1944.

On politeness and civility

by Valera

Is there an evolutionary advantage in being polite? Don't we undermine the survival of the fittest by being nice, polite and tolerant to the weak, obnoxious or annoying? Isn't the fundamental principle of good manners - the one that makes it impossible to point to others their lack of manners - extremely stifling and preventing any potential spread of civility onto hoi polloi, the great unwashed, therefore threatening its own "survival"? In other words, can, will and, ultimately, should politeness survive?

There have been studies in altruism, which tried to explain it in terms of possible genetic advantage. Ironically, the explanation made sense only if the survivor of the situation was not the human carrier, but the altruistic gene. So, the theory goes, sacrificing oneself for the close kin only makes sense, since it maximizes the survival of the copies of the gene. But politeness seems to be a mechanism of coping with strangers, awkward and embarassing situations, and at the first glance, irrelevant to the genetic advantage.

As Benedetta Craveri wrote, politeness was indispensable if one were to "dominer la violence des instincts, élever des remparts contre brutalité de l'existence, interposer entre soi et les autres un bouclier invisible susceptible de garantir la dignité de chacun".

Here we may have stumbled on the solution to the problem - the key word is "dignity". Politeness may have emerged as the means to avoid duels, invariably lethal to at least half of the contestants. To have all the money in the world - and then having to die for the slightest hint of suspicion of a shadow of intent to malign one's honour! O, cruel world! Strangely enough, the closest inheritors of that obsession with dignity are the dispossessed - the poor member of the modern inner city gangs, which have developed extremely rigid codes of securing "respect" (my apologies to the Northeastern WASPS).

Nearly all Eastern Europeans coming to the U.S. for the first time feel urge to comment on excessive American habit of fake smiling and shallow politeness. The American underclasses experience the same unease around the representatives of upper classes. Cultural and class distinctions closely correlate with starkly diverse ideas of honor, dignity and the code of conduct - yet, all people agree that a certain set of rules, codifying behavior is absolutely necessary to simplify the, eh, intercourse. This is not I, this is "Daisy Eyebright" in her "Manual of Etiquette":

How to diminish friction; how to promote ease of intercourse; how to make every part of a man's life contribute to the welfare and satisfaction of those around him; how to keep down offensive pride; how to banish the rasping of selfishness from the intercourse of men; how to move among men inspired by various and conflictive motives, and yet not have collisions -- this is the function of good manners.

to be continued...

TLS 10-14-05: No song without words

by James Fenton

I was looking for a text that would help me express what happens when words and music come together, but I chanced instead on a different thought: that there was once no place for a music without words, that a purely instrumental music was a concept that had no content. The aesthetics of European music, so I read, had their origins in Greek thought, and our musical theory was developed in the womb of the Catholic Church. There, until around the middle of the eighteenth century, music was held to be meant exclusively for the glorification of God, and this glorification should always be made through words. And from this argument, I was informed, came the resistance to the emancipation of instrumental music, the condemnation, the demonization of it. This notion came fresh to me, as it seemed to come fresh to the subject of an interview I was reading, Hans Werner Henze, for the composer asked, “Who actually is the chief representative of this school of thought?” and was told by the somewhat evasive interviewer, “That was the general opinion of the theoreticians of those days”.

No music without song, no song without words, no words without the praise of God – a stern theory, and one which has its echo a few pages later in the interview...

see full text in the TLS the October 14 2005 issue

Labels: TLS

October 25, 2005

TLS 10-14-05: The Virtuoso Liszt

By Dana Gooley

Franz Liszt, still often thought the greatest of all pianists, made his mark as an international virtuoso mainly during a period of less than a decade. From 1838 to 1847 he criss-crossed Europe with frenetic energy, presenting more than 1,000 concerts from Madrid to St Petersburg, from Constantinople to Manchester. Heads of state conferred on him singular honours: the Order of Carlos II in Madrid, the Order of the Lion of Belgium in Brussels, the “sabre of honour” in Pest, and (perhaps with rather different implications ) two trained bears from Tsar Nicholas I in St Petersburg. Tumultuous ovations greeted him almost everywhere.

In 1838, a series of six concerts in Vienna became ten by popular demand; Berlin in 1841–2 enjoyed a ten-week stretch of twenty-one concerts, filled to overflowing, at which Liszt performed some eighty works. Especially in that city, Liszt seems to have aroused a kind of hysteria, for which Heine coined a name, “Lisztomanie”. Well-situated women collected the pianist’s hair-clippings, it was said, and wore his discarded cigar butts on their persons; he received the Ordre Pour le Mérite, and departed the city along Unter den Linden in a procession of thirty carriages drawn by white horses, as the King and Queen of Prussia waved from a palace window...

Liszt’s visit to Hungary in 1839–40. Though born in that country (of German-speaking parents), he had as an adolescent taken up residence in Paris, and had never thought of himself as Hungarian, nor spoken the language. Yet on Liszt’s first visit to that country since childhood, the conservative Magyar political forces, aflame with nationalist enthusiasms, hailed him as a national hero and conferred on him the sabre of honour....

see full text in the TLS the October 14 2005 issue and the book description at the Cambridge University Press site.

Labels: TLS

Love/Hate relationship

by Valera

Isn't it strange how the Middle East teenage population wears American T-shirt and yet is staunchly anti-American? They drink Mountain Dew, but ready to spill the infidels' blood. They adore Hollywood movies, but ready to kill any American. They would love to have a Cadillac and a pool and a digital camera and a plasma TV and use Internet, and yet, and yet, and yet. Is it irony? Is it oblivion? Is it desperation?

On consensus and freedom to have none...

Having recently heard a quote of Margaret Thatcher "Consensus is just the lack of leadership" I could not but recall the utter disgust I experienced every time I have spoken with a C level executives. Because of my "red" origins, they all sooner or later commented on communism and lack of freedom of speech and expression there, as opposed to exuberant free market and the liberties it conferred on lucky Americans. The presumed victory in the Cold War over the Russkies invariably sets these people in a self-congratulatory mood. When reminded that the biggest Communist country in the world is still alive and well; or, moreover, that it manufactures a substantial part of all the consumer goods in America - these folks uncomfortably twitch, probably not unlike Nixon who had to swallow his pride and offer friendship to his Chinese counterparts.

What disgusted me was not the noxious regurgitated propaganda, but the degree with which each and every one of them expressed their intolerance towards employees who disagreed with their views or leadership; the vehemence and resolve with which they assured me that there was no place for people like that in their enterprise, that this was a free country, and therefore these people were free to pursue their free will elsewhere, just not here.

Is freedom then ultimately a liberation from the need to build consensus? Is freedom just an opportunity to wander off into the West and live as one thinks one wants? Is freedom mostly lack of desire to live with others? Is freedom an ability to choose what one wants and whom one wants? Is freedom simply an option to avoid dealing with the Others, a permission to eradicate dissent by shooting any trespasser, even an imaginary one? Is it the same alpha-maleness, that unreigned desire to mark the territory with spit, blood and urine and fight any other perceived or real contender that one observes in some species?

October 24, 2005

My personal world map

Where I have Been

KLM now offers great visual aid to see how "local" we truly are. One can see all the countries one has been to.visited 22 countries-

like to visit 2 countriesCreate your own world map

StressEraser

With the StressEraser you can calm your mind and relax your body anytime, anywhere—even during intensely stressful life events.

You can use the StressEraser to:

- Quiet your mind before sleeping

- Relieve intense stress

- Reduce chronic stress

- Free yourself from worry

- Keep calm during stressful events

- Relax whenever you want

Helicor offers a 60-day risk-free trial of the And what is the price of that little piece of mind? I will let you discover it by yourselves! Click here to go to the company website

I just love that button that says BREATHE, what would I do without it :)October 23, 2005

Robert Doisneau

Selection for the Concert Mayol music hall, 1952. From Robert Doisneau's Paris ed. by Francine Deroudille and Annette Doisneau (400pp, Flammarion, ISBN 2 0803 0491 7)

Bridge of Millau

Now here is a marvellous proof that God does not need to exist and that intelligent design is exactly just that :) You can actually visit the bridge's web site and see the traffic on the bridge in REAL TIME!

Alena Akhmadulina

What a young Russian stylist to do for her first ever fashion demonstration in Paris? How does one stand out in a crowd of hundred competitors, fighting for the attention of the press and the buyers? Here's how! :) | |||

Rossy de Palma

| L'égérie d'Almodovar au visage cubiste n'est pas seulement une actrice de caractère. C'est une géniale touche-à-tout! | |